By Gemma L.

The contrast between the romantic glamor and the shadowy true nature behind those dazzling times caught my interest.

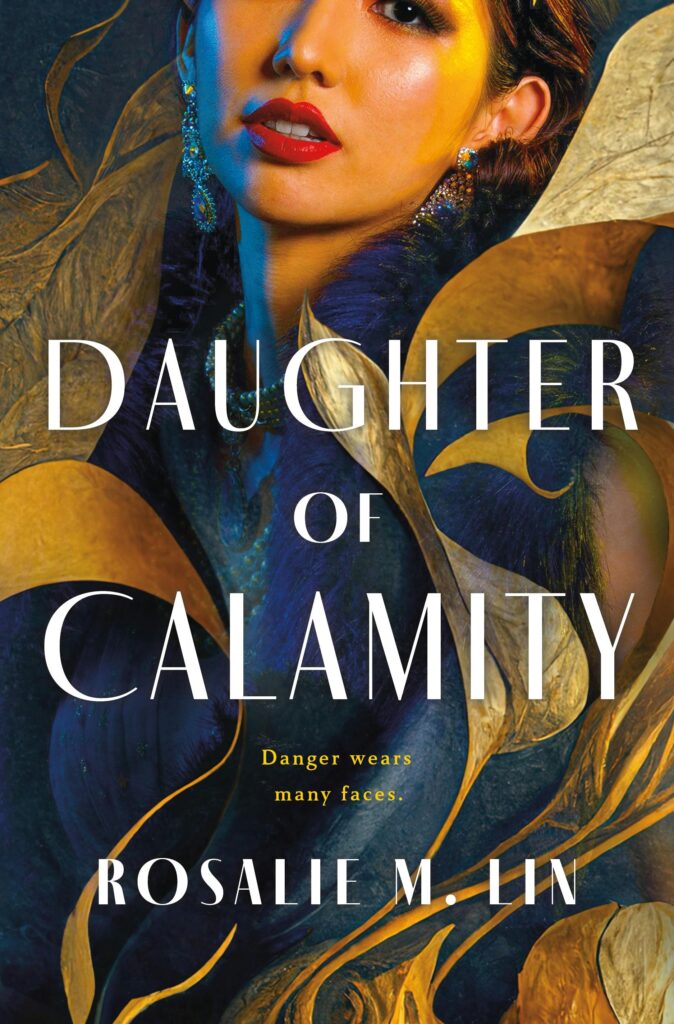

Gemma: Your debut novel, Daughter of Calamity, is a dark historical fantasy set in the jazz age of Shanghai. The book features gods, gangsters, family and betrayal, and girls who take control of their own destiny. What compelled you to write a book like this?

Rosalie: I was drawn to Jazz Age Shanghai because the city was so glittery and glamorous at the time. However, that opulence was a mirage, and all the bustling business and nightlife in 1930s Shanghai was only possible because after the First Opium War, Shanghai was partitioned by eleven foreign nations. The contrast between the romantic glamor and the shadowy true nature behind those dazzling times caught my interest. I wanted to write the story of a girl caught between both sides, and also delve into how the shifting politics and worldviews (embracing vs rejecting colonialism, eastern vs western values, etc.) would play into her life.

Gemma: Your main character, Jingwen, is so fascinating. She is a dancer by night, and a smuggler even later than that. She is set to be an apprentice for her grandmother who performs operations on the gangster elite of their city. But beyond all of that, just who is Jingwen?

What makes her extraordinary is her decision to rise up and dismantle a system much larger than her, without changing who she is at her core.

Rosalie: I love how you phrased that! “A dancer by night, and a smuggler even later than that.” Well, at her heart, Jingwen is a city girl caught between her traditional-minded grandmother and her dreams, who has a decent number of things going for her, but always happens to be second best. This situation is made several-fold more complicated by the fact her grandmother is the surgeon for the Blue Dawn, Shanghai’s most notorious gang. I view Jingwen as an archetypal modern girl—she is a consumer and a mass market feminist who loves makeup and pretty things. She embraces her sexuality and loves her financial independence. However, the grandmother situation makes it difficult for Jingwen to embrace her exciting life as a cabaret dancer, as her grandmother places significant pressure on her to become her apprentice and someday inherit her title as the Blue Dawn’s surgeon. Such a bind might be relatable for anyone who grew up between two cultural outlooks and is struggling to reconcile the two. On her own, Jingwen is not anybody special—what makes her extraordinary is her decision to rise up and dismantle a system much larger than her, without changing who she is at her core.

Gemma: Chapter one instantly hooked me, but what stood out the most was your beautiful writing. There is a dreamlike quality to it that felt very poetic throughout. Was this an intentional stylistic choice or just how you write?

Rosalie: I’m so glad you used the term “dreamlike!” When I was doing research for Daughter of Calamity, I made it my goal to delve into non-Western perspectives of 1930s Shanghai. I read books and short stories by Chinese and Japanese authors who lived in Jazz Age Shanghai and discovered a movement called Postmodernism in Asian literature. These stories, which took place in cabarets and factories, often featured moody middle-aged men going through midlife crises. However, these stories also had a heavily atmospheric style where quiet city streets would become somewhat ominous, reflecting the characters’ internal dread. I wanted to write about a young girl during the time, but borrow from this overwhelmingly atmospheric style, using the setting to reflect her emotions.

Gemma: In this book, there is a competition between Jingwen and the other dancer girls which later shifts as the story progresses. By the end, I understood this to be a showcase of female empowerment and sisterhood in the decisions Jingwen made. Is my interpretation correct or was there another intention you had in mind?

Rosalie: Yes, that’s spot-on! Jingwen lives in a patriarchal society with many systems in place to keep women from discovering their power. At the cabaret Jingwen dances at, she and the showgirls are set up to fight each other over rich, foreign men. It takes all the events in the novel for the girls to eventually realize that they are a stronger force united. Moreover, Jingwen is often lonely in the beginning of the book—she comes to realize that her stiffest competitors, the other dancers, are the only ones who understand her struggles and triumphs in life. That is my favorite plotline in the book! The women discovering their deadliness and finding comradery in that discovery.

Gemma: There are a number of gods that play a role in the book, some that I recognize and some that admittedly, I do not. Were there any inspirations from mythology that you pulled, and were there any liberties you took?

Rosalie: It was so fascinating to delve into comparative myth while writing Daughter of Calamity! Many mythologies and religions feature a “mother” deity figure, and I really wanted to explore how this mother deity figure was translated from one mythology to another. If you’ve ever been to a Chinese restaurant, you may have noticed a shrine dedicated to a particular goddess, who also happens to be the major goddess who appears in Daughter of Calamity – Guanyin Boddhisattva, the central female deity in Buddhism. However, in Daughter of Calamity, she appears not only as Guanyin, but also as her counterpart in Daoism, the Queen Mother of the West. Rather than an auspicious goddess called upon to bring protection to the family business, the Queen Mother of the West (or Mother of Calamity) was a demon who found enlightenment—a much more feral figure. However, this translation gets even more interesting. Growing up, I knew Guanyin as the Goddess of Mercy (her Wikipedia page states as much)—however, this moniker “Goddess of Mercy” was actually given to her by Christian missionaries in China, who likened her to the Virgin Mary. Just like Jingwen, who comes of age in a metropolitan environment of many clashing cultures, I wanted to explore how an ancient goddess might have to deal with the identity crisis of being caught between Ancient China and the Jazz Age/partition of Shanghai.

Although she does not fight with a sword as the gangsters do, she is equally powerful in other ways.

Gemma: Another major character is Jingwen’s grandmother, who has ties to the gangster elites, and Jingwen’s loyalties to family are tested. How did you create this tension and how does it give Jingwen agency in choosing her path?

Rosalie: Jingwen embodies a very feminine flavor of power—she recognizes that Shanghai’s nightclubs are paramount (no pun intended) to the city’s fame and reputation, and that although she does not fight with a sword as the gangsters do, she is equally powerful in other ways. There are not many examples of feminine power around Jingwen in 1930s Shanghai, and this is something she discovers for herself. On the other hand, Jingwen’s grandmother Liqing represents a traditional, masculine flavor of power. Although Liqing is a woman, she rose to prominence as a notorious gang’s surgeon, a position historically occupied by a man. Liqing wishes for Jingwen to become powerful like herself, but she does not understand or accept Jingwen’s definition of power. Jingwen, through the tension with her grandmother, learns to embrace her own definition of power—that her feminine power is no less meaningful or deadly.

Gemma: Jingwen’s primary career is as a dancer, and art plays a large role in this book. As a writer, the freedom of creativity and expression must mean a lot to you. Why is this a theme in this book?

Rosalie: These days, China is a place where freedom of expression and creativity are strictly limited. In fact, when the Republic of China was founded less than two decades after the events of Daughter of Calamity, the Paramount Ballroom was shut down (although today it has been revived again), and dancing was banned. The 1930s was a golden age of music, dance, and the arts in China, before these restrictions came into place. I guess I turned to this era out of nostalgia and curiosity.

Gemma: What do you want readers to take away from Daughter of Calamity?

Rosalie: I hope Daughter of Calamity provides some food for thought about feminine power, mythology, cultural appropriation, and colonialism.

Gemma: We’d like to hear more about yourself as well!

Daughter of Calamity is your debut novel and highly praised by other authors. What has the reception from the book community been like for you?

Rosalie: The book community is one of the most supportive communities I’ve had the honor of being part of! My favorite part of the publishing journey so far has been getting to visit all these lovely indie bookstores across the country and chatting with readers. I feel like every indie bookstore has its own special personality and bookish community, and while I’m familiar with my local bookstores, it’s so cool to travel and visit other bookstores and bookish communities around the world. Also, since Daughter of Calamity is a heavily atmospheric novel, I absolutely love it when readers post aesthetics and artwork. Every single one I’ve seen so far has nailed the vibe. A reader at an event made a shadow box for Daughter of Calamity with such accurate, intricate details—I still marvel over it every time I walk past my bookshelf.

Gemma: Before becoming an author, you’ve had a variety of careers and interests. Could you tell us more about the path you’ve taken to finally becoming an author?

Rosalie: Being an author was the first career I ever dreamed of as a kid, and also the last career I’ve decided on as an adult. I’ve wanted to be an author since I was eight years old. I was very adamant about it and spent almost all my free time writing throughout high school (I queried my first novel when I was 14!). However, when I was young, I had a lot of insecurities and I was not equipped to deal with rejection as well as I thought I was. Eventually, the rejection got to me—I compared myself too much to others, and I stopped writing. I explored a plethora of other careers in college—clinical psychology, political science, law, and medicine. I even considered moving to Beijing to open a women’s gym. I’m grateful for that era of exploration because I got to dabble in a lot of different worlds, which has kept my creative brain nourished. I guess I’m also grateful because I live in a high-cost-of-living city, and during the years I drifted away from writing, I managed to establish a decent-paying career with a nice PTO package. Eventually, I realized that writing stories was my true passion—the only thing I still returned to after twenty years (whereas I had gotten bored with every other career I explored). I have a deep desire to share my stories about the Chinese American experience, generational trauma, dancing, and beautiful worlds. I feel very lucky I have a way to do so!

Being an author was the first career I ever dreamed of as a kid, and also the last career I’ve decided on as an adult.

Gemma: Before becoming an author, you’ve had a variety of careers and interests. Could you tell us more about the path you’ve taken to finally becoming an author?

Rosalie: Being an author was the first career I ever dreamed of as a kid, and also the last career I’ve decided on as an adult. I’ve wanted to be an author since I was eight years old. I was very adamant about it and spent almost all my free time writing throughout high school (I queried my first novel when I was 14!). However, when I was young, I had a lot of insecurities and I was not equipped to deal with rejection as well as I thought I was. Eventually, the rejection got to me—I compared myself too much to others, and I stopped writing. I explored a plethora of other careers in college—clinical psychology, political science, law, and medicine. I even considered moving to Beijing to open a women’s gym. I’m grateful for that era of exploration because I got to dabble in a lot of different worlds, which has kept my creative brain nourished. I guess I’m also grateful because I live in a high-cost-of-living city, and during the years I drifted away from writing, I managed to establish a decent-paying career with a nice PTO package. Eventually, I realized that writing stories was my true passion—the only thing I still returned to after twenty years (whereas I had gotten bored with every other career I explored). I have a deep desire to share my stories about the Chinese American experience, generational trauma, dancing, and beautiful worlds. I feel very lucky I have a way to do so!

Gemma: In addition to being a writer, you also mentor for Pitch Wars, a writing mentorship program. Do you have any advice for those who also want to publish someday?

Rosalie: I am so grateful I got to mentor for Pitch Wars during the last year of the program. My advice for aspiring writers is to know why you’re writing, and hold that reason close to your heart. Always. Being an author can be a roller coaster career, fraught with rejection and comparison against others. For me, this is the hardest part of the process. During these tough moments, I remind myself why I still write, when I could easily just stop and spend my evenings watching TV with my cat instead.

Gemma: I absolutely love your author’s voice and am looking forward to your next book! Do you have anything in the works that you can tell me about?

Rosalie: At this point, I can share that it will be another adult historical fantasy! It will be completely unrelated to Daughter of Calamity, but it will likely involve assassins and ancient China.

Gemma: I understand that you’re a K-Pop fan, and a dancer as well! What can be found on your playlist? What are your favorite K-Pop songs to dance to?

Rosalie: I love dancing to LE SSERAFIM and aespa—anything girl crush, really! I listen to K-Pop on my morning walks to get coffee. K-Pop energizes me.

Gemma: Last question: Can you tease our readers with a line from Daughter of Calamity?

Rosalie: “In Shanghai, everybody wears multiple faces. Even the streets have more than one name—the temples, the banks, even the Paramount. Some mornings when I walk home alone at the break of dawn, I think about how terribly lonely it is to live in a place like that—a place where you can never really know anyone.”